The United States Withdrawal from Afghanistan

The United States Withdrawal from Afghanistan

Imperial Hubris: The Great Game Revisited

By Jack Carr, Published on 08/16/2021

It was inevitable. Or was it?

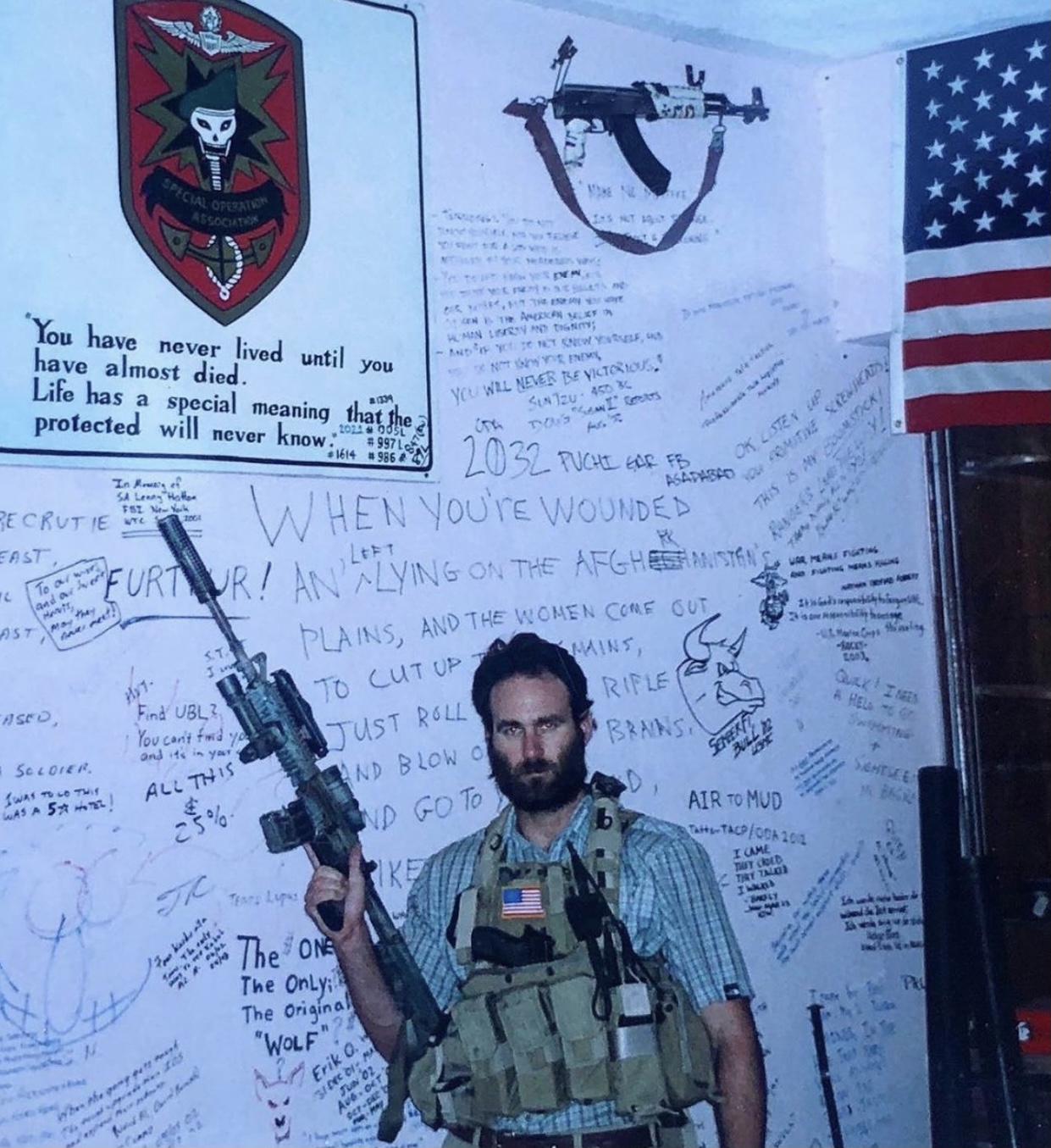

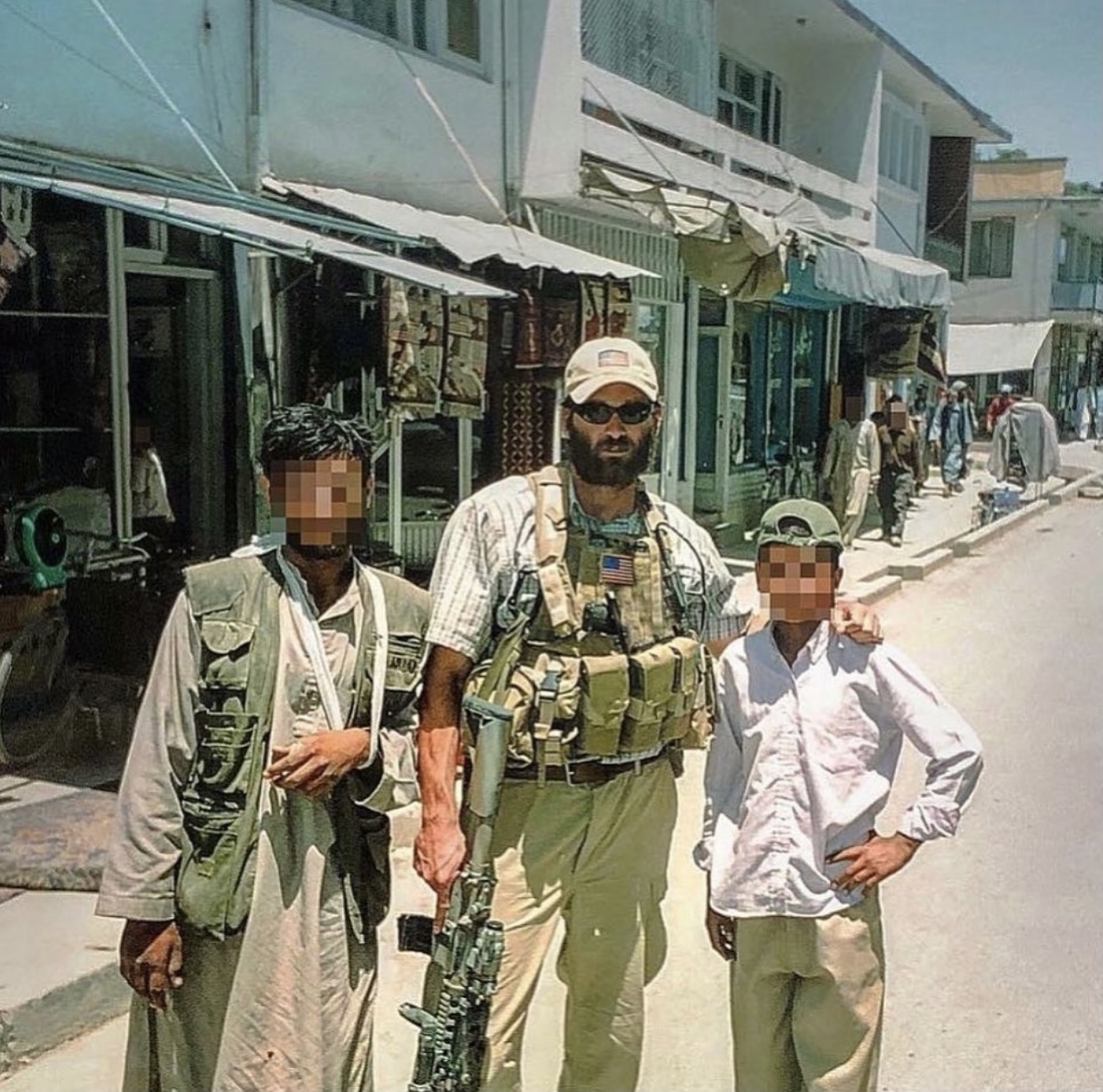

“The Americans have all the watches, but we have all the time.” I first heard this saying in Afghanistan in 2003 from a former mujahadeen who fought against the Soviets. Its precise origin is unknown, but it certainly applies, and from that point on I examined all U.S. tactical and strategic efforts through the prism of that very simple and accurate adage. It made such an impact that the quote is in the first paragraph of chapter one of my 2018 debut novel, The Terminal List.

September 11, 2021 marks the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attacks that propelled the United States into Afghanistan. This year, for the first time in U.S. history, one could have joined the military, served for twenty years, and retired while the country is still involved in the same war. That should give us pause. As Dr. David Kilcullen notes, the enemy was prepared with a strategy they have used against invading armies for centuries: Provoke – Intimidate – Protract – Exhaust. Our enemies have figured out how to not only effectively counter but defeat the most technologically advanced military on earth. In what is accurately described as imperial hubris, the United States political-military establishment confused entry and initial resolve with victory. They were wrong; America’s sons and daughters paid the price.

In April of this year, I wrote,

“if withdrawal from Afghanistan proves popular with the American public, then President Biden will take credit for what was a Trump Administration plan. If it proves unpopular or disastrous, then President Biden will blame the previous administration.”

BREAKING: Dozens of nations call for peaceful departure of foreign nationals and Afghans who wish to leave Afghanistan. https://t.co/hI8U0BIQ04

— The Associated Press (@AP) August 16, 2021

While true, it does not accurately portray what was a whole of government failure, a failure that crossed party lines over four separate administrations, two Republican and two Democrat. As we watch the U.S. Embassy evacuation in Kabul and see images of the Taliban taking control of the country, to those of us who fought there it is more than a strategic failure; it’s personal. Our senior political and military leaders failed those service men and women they sent into harm’s way. As a nation we failed the soldier, sailor, airman and Marine who stepped up in service to the nation following 9/11. We owed them better. We owed their families better. And we owed our country better.

“The Americans have all the watches,

but we have all the time.”

“The Americans have all the watches, but we have all the time.”

– Afghan Saying

How did this happen?

Simply put, our elected officials and senior level military leaders were trapped by their own intellectual inertia, condemning us to eventual defeat.

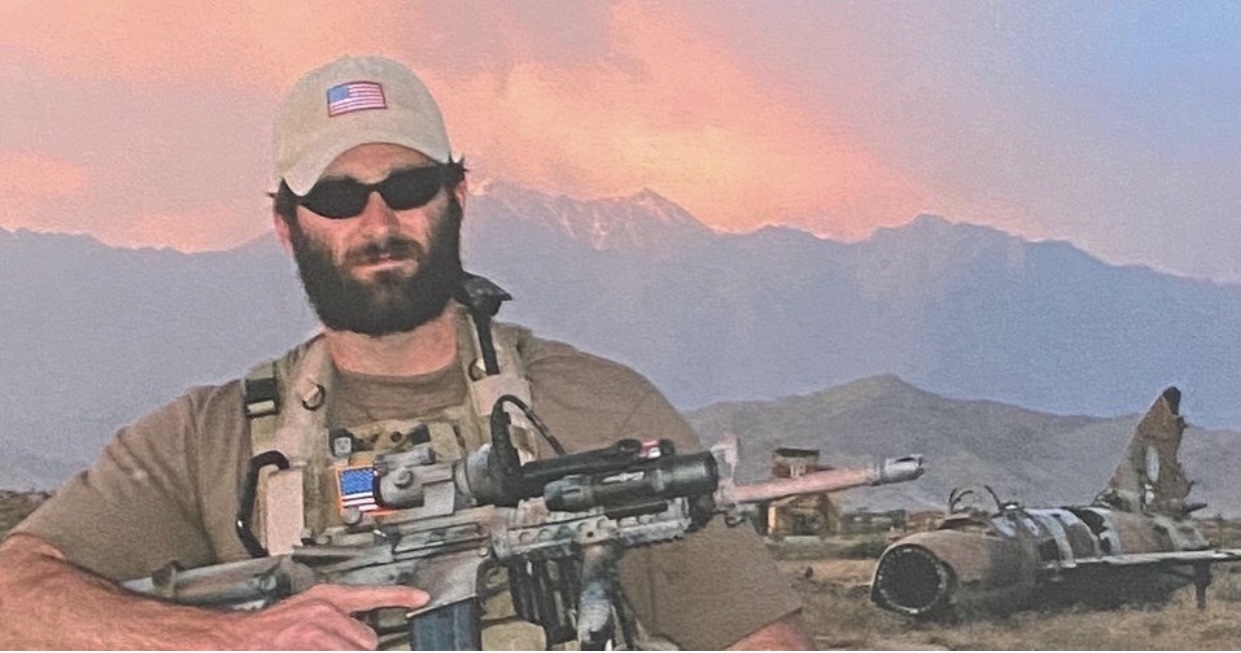

On September 12, 2001, the day after 9/11, I briefed my platoon and the commanding officer of Naval Special Warfare Unit One in Guam on Afghanistan, al-Qaeda and the Taliban. As the SEAL intelligence specialist for the platoon and a lifelong student of history, warfare, terrorism, and insurgency, I covered the recent and not so recent history of Central Asia from the perspective of, although I did not use these exact words at the time, understanding the nature of the conflict in which we were about to engage. Today’s outcome was obvious to a twenty-something E-5 shooter in the SEAL Teams, which begs the question, how was it not obvious to those policy makers and senior level military leaders whose job it was to understand the strategic level implications of their decisions?

Without an intricate understanding of Afghanistan, its history, people and culture, an eventual U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in defeat was inevitable. That inevitability could only have been thwarted through studying the past, heeding its lessons and applying them to the conflict. The 19th and 20th centuries were replete with case studies — case studies that were ignored.

Should Afghanistan’s reputation as “The Graveyard of Empires” cause us to further evaluate our strategies and intent? Should the history of the massive and brutal military campaigns of Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Timur bogging down in Afghanistan inspire us to put the requisite time, energy, and effort into the study of those wars to extract their lessons? Should the more modern experience of the three British Anglo-Afghan Wars and the Soviet invasion and occupation guide our strategy? We had firsthand experience supporting the mujahadeen to counter the Soviets in the 1980s. After the U.S. entered Afghanistan in 2001, allied forces occupied positions that were built on British forts abandoned over a hundred years earlier. Some would call this foreshadowing. I returned home with a rifle as a reminder of my time there. I mounted it to the wall in my office as a physical reminder of what that former mujahadeen told me in 2003. It’s an Enfield muzzle loaded musket. It was made just outside London. A date is stamped into its metal: 1864.

United States military and political leaders did not understand the nature of the conflict to which they were committing America’s sons and daughters; their strategic level decisions were abject failures. While politicians and their appointed advisors failed on the policy front, our military leaders were never held accountable for their poor performance at the strategic and operational levels. Accountability has been a critical part of our military operations since the founding of our nation. That began to change in the 1960s. General Washington did so during our war for independence. President Lincoln did so in the Civil War. George Marshall did so before and during World War II. As Georges Clemenceau put it, “War is too important to be left to the Generals.” Tactically, on the battlefield, we were held accountable for our mistakes.

Strategically, our leaders were not held to account for their blunders — in too many cases, blunders of epic proportions. Rather, they were promoted and eventually retired with full pensions to sit on the boards of companies making a killing in the world of government contracts; the military industrial complex is alive and well. As Lt. Col. Paul Yingling pointed out in his 2007 article A Failure in Generalship, “As matters stand now, a private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war.” This remains true fourteen years and three administrations later.

“As matters stand now, a private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war.”

– Lt. Col. Paul Yingling

What were America’s strategic interests in Afghanistan?

How many politicians have an answer to that question if asked by the mother or father, son or daughter, husband or wife of a fallen servicemember?

Our Initial goals were to disrupt al-Qaeda operations and destroy the al-Qaeda organization. We made rapid progress in those opening months of the conflict in what Carl von Clausewitz would have called “the culminating point of victory.” The men and women on the ground from our military and intelligence services came within a stone’s throw of decapitating the organization and destroying enough of it to set them on their heels. What we failed to do was recognize that al-Qaeda was more than a physical organization of terrorists, leaders, bombmakers, and facilitators; al-Qaeda was an idea, and ideas are harder to kill than human beings made of flesh and blood. After our initial success on the battlefield, we “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory” as our political leaders switched gears to reconstruction and nation building, shifted focus to Iraq, and attempted to counter corruption (bribery, extortion, drug trafficking) endemic in the new Afghan government, one modeled after the United States and our allies in Europe.

Any terrorist network or insurgency needs a sanctuary.

For a tribal people who don’t recognize borders on a map, especially a map drawn up by western invaders, neighboring Pakistan and Iran posed difficult political problems that directly resulted in dead Americans on the battlefield. Those countries had a vested interest in the United States not becoming a permanent presence in the region. Offering sanctuary to insurgents and terrorists on the other side of borders we recognized, but our enemy did not, allowed that enemy to rest, recover, refit, plan and train beyond the reach of American power. Leveraging cross-border sanctuary should come as no surprise – it was widely known and reported, yet, with few notable exceptions, we took no action to address it. The United States failed to recognize that Middle Eastern and Central Asian nations have been trading borders since the Old Testament. This history, coupled with our lack of understanding of it, ensured that we would become bogged down in twenty years of conflict. Osama bin Laden was killed in Pakistan in May 2011 and Abu Muhammad al-Masari, al-Qaeda’s second in command, was killed in Iran in August 2020. Also killed in that attack was the widow of Hamza bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s son. Those HVIs were not in Pakistan and Iran by chance.

Modern expeditionary counterinsurgencies favor the insurgent, not the counterinsurgent.

We have our own experience in Vietnam and the 1979 – 1989 Soviet involvement in Afghanistan to study. These are lessons from the pages of history. The responsibility of senior level leaders is to apply those lessons to their decisions in the form of wisdom. We have all heard variations of philosopher George Santayana’s famous maxim: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Of course, a strategy based in historical understanding can still fail greatly when tested in complex environments against an adaptive enemy who gets a vote, but it almost certainly enables a solid foundation from which to build and execute. Would studying the past have resulted in a different outcome in Afghanistan? Not necessarily, as it is certainly possible to study the history, culture, politics, language, economy, religion and tactics of the enemy and still make strategic mistakes. Even the smartest among us can fall prey to the traps of ego and hubris, but here is a difference between being smart and being wise. It is also telling that George Santayana wrote the chilling line often attributed to Plato: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

Even more unsettling is the example we have of modern empires, Great Britain and the Soviet Union, declining in the wake of incursions into Central Asia. The world’s geopolitical power paradigm shifted following their misadventures in Afghanistan. Will the United States suffer the same fate?

History indicates that the goal of insurgencies is to eventually rule.

As the Taliban once again moves from an insurgency to an established government, what will that mean for the United States? Prior to September 11, 2001, Afghanistan was a hotbed of terror with multiple terrorist training camps in operation across the country. Terrorists from all over the world would travel to Afghanistan, primarily through Iran and Pakistan. Will it once again become a magnet for terrorist activity? Technological advances over the past two decades have made physical sanctuaries less imperative for terrorist training and planning. Much of that can now be done virtually. Capitalizing on a physical base of operations and a virtual planning and recruitment space with global reach is a powerful combination.

As I watch Afghanistan fall to the Taliban, I remember my friends who fought and died there, I think of all those who are permanently disfigured from their time in combat, forever dealing with the physical and emotional trauma of the battlefield. I think of the bravery of those who stood up in the wake of September 11, 2001 to bring the fight to an enemy who had attacked the homeland, and I seethe with resentment and disdain at the politicians and senior level leaders who failed those brave patriots and their families, leaders who sat in their temperature controlled offices in the Pentagon, the halls of Congress and the White House and fell victim to imperial hubris. How can we honor those who gave so much? We can take these lessons and apply them to future decisions in the form of wisdom. In the end, that’s the least we can do for those who didn’t come home.

If world history is any indication, we will not be the last country to attempt to intervene and occupy Afghanistan. The next should remember with more than a passing interest that “the Americans have all the watches, but we have all the time.”

Going forward we would be wise to remember the past. And learn from it. For a change. The next generation of frontline troops deserve no less.

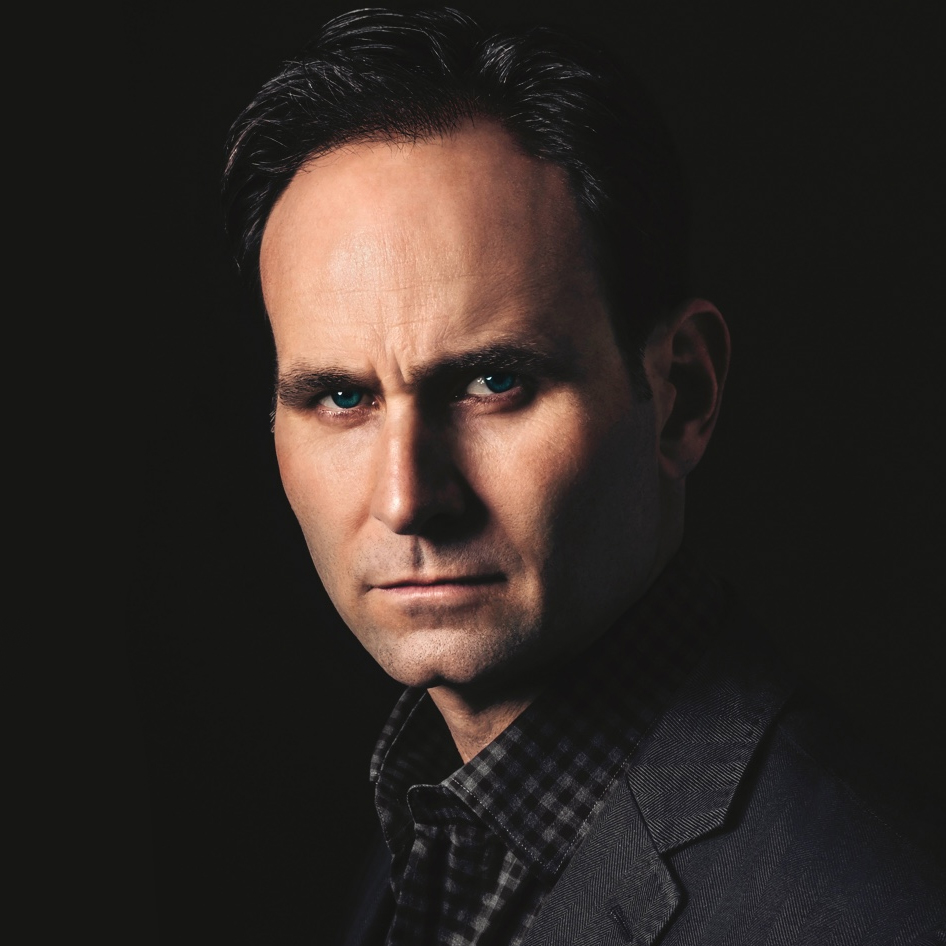

Jack Carr is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Devil’s Hand and host of the Danger Close Podcast. He is a former Navy SEAL Task Unit Commander and Sniper with deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq.

FICTION WITH WHISPERS OF TRUTH

Applying the experience and emotions from real-world combat to the pages of his novels, Jack Carr brings unprecedented levels of authenticity to the political thriller, taking readers on a behind the scenes journey into the mind of a modern-day special operations soldier.